IRA = Irish Republican Army, an armed and underground organization created in 1919, whose aim is to liberate the entire island of Ireland from British occupation by violence

RUC = Royal Ulster Constabulary, a Northern Irish state police force, created in 1922 and made up mainly of English and/or Protestant members.

UVF = Ulster Volunteer Force. Paramilitary organization founded in 1966. It is the English counterpart of the IRA. Declared a terrorist organization by the United Kingdom in 2000

The Troubles: a separate habitat, an unequal society, a government far away behind an arm of the sea , demonstrations that get out of hand, a spiral of violence. To understand the duration of the conflict and its deep roots, we should take into account the fact that the Troubles and their resolution happened on four levels:

• Civil and religious

•Paramilitary

•Penitentiary

•Political

It took 30 years, a death toll of 3,720, nearly 37,000 shootings, more than 16,000 explosions and two Nobel prizes to resolve the conflict. Two-thirds of the deaths were caused by the IRA, 23% by the UVF and 10% by the British Army. Here are some explanations on the reasons for the duration and violence of the conflict.

Things don’t happen by chance, or all of a sudden. In the early 1960s, there were about 65% Protestants and 35% Catholics in Northern Ireland. Each community had its own life, but it was the Protestants who had absolute control over the political and economic life of the province. In these times however, three things were changing:

• The emergence of a new generation : better educated than their parents thanks to the free public education system, they had no intention of staying on the edge of society

• The emergence of civil rights movements in various countries, notably the USA, and the creation of the NICRA (Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association) in Belfast on the model of Black Civil Rights

• The election of Terence O Neill as head of the province in 1963 : he was driven by a real desire for economic modernization and rapprochement between the two communities

The coexistence of a mainly student community in turmoil and a prime minister who was both conservative and reformist (he even mentions « a new dawn » for Ireland) in front of a society whose firmly established order was turned upside down, that was the starting point of the Troubles. This pacific movement for civil rights thus clashed with the power of the Protestants, a power that was at once political, economic and social. Furthermore, the loyalists had well-established rites (religion, marches, etc.) . Those same rites ignited the powder. Indeed, Orangemen were accustomed to regular marches and did not accept that civil rights activists in turn organized marches. In 1968, a civil rights march was challenged by a march of the Protestant Apprentice Boys of Derry. The march took place despite a ban by the authorities and was harshly repressed by the RUC. The violent repression received worldwide media coverage. This is the beginning of the Troubles.

Small reforms were introduced, which were largely insufficient for the Catholic community, a number of whose members began a long march between Belfast and Derry. Arriving at Burntollet Bridge on 4 January 1969, they were attacked by hardliners and the RUC did not much to help them. This sparked several days of rioting. From the beginning, Protestants felt threatened (and this is one of the keys to understanding the conflict) and, under the banner of the UVF, some of them blew up a series of domestic infrastructures while blaming the IRA. It forced O Neill to resign.

It was in this tense context that the annual demonstrations of the Orangemen took place in Derry, which celebrated the victory of the Protestant William over the Catholic King James in 1690. It is de facto a strong symbol for the Protestant and Unionist community. On the 12. August 1969, a demonstration turned ugly when the RUC fired tear gas on the population of the Bogside, the Catholic district of Derry, for the first time in the United Kingdom. The riots spread to Belfast, and Catholic houses were burned. The events of the summer of 1969 had 3 lasting consequences:

• The construction of the walls, the infamous Peace Walls. They were built as early as 1969, to both separate and protect the population.

• The revival of the IRA, hitherto unpopular even among Catholics.

• The arrival of the British army, theoretically on the scene to pacify the population, in practice in support of the British section of the population.

And that’s how riots were answered by the force that brought violence, and so on. A vicious circle was set up that lasted 30 years. For more than a generation, between negotiations and car bombs, the daily life of the inhabitants was punctuated by separation, segregation, bomb threats and police checks.

By September 1970, the IRA and UVF had detonated 100 bombs and killed 21 people, and this was only the beginning. From London, the government looked with a certain disdain on this province and what was wrongly considered to be short-term riots. The home secretary in charge of Northern ireland even said on his way back from a visit : « What a bloody awful country. For God’s sake, bring me a large scotch ! »

Violence simmered until Sunday, January 30, 1972. On that day, a civil rights march was announced in Derry. Wanting to strike hard, the British government had sent paratroopers in advance, in order to « subdue » potential excesses and the movement in general. Paratroopers opened fire on unarmed protesters, killing 13 people. The victims are still laid to rest side by side in Derry Cemetery today. This caused a scandal, and Dublin recalled its ambassador to London. After what History straight away called « Bloody Sunday », the violence of the repression gave the IRA a strong boost in notoriety, and many young people joined the underground organization.

On a societal level, it must also be understood that there was a real intolerance on both sides. On the Protestant side, the pastor and politician Ian Paisley went so far as to say that Catholics « breed like rabbits ». His repeated speeches hit the nail on the head with a large part of the population, mainly the working classes. On the Irish side, the IRA wanted to ‘liberate’ the whole island of Ireland from British occupation and advocated violence. They even did not shy away from cracking down on catholic people considered traitors. This is how the year 1972, the dark year of the Troubles, ended with the kidnapping and murder of Joan MC Conville. She was a widow of a Catholic, herself a convert, and mother of 10 children. She had been accused by the IRA of having helped a seriously wounded British soldier and regularly informing the British. Later Investigations have clearly refuted the second accusation, and the first amounts to a heavy punishment for an act of Christian charity, which would be ironic in that specific context if it were not cynical. The fact is that Joan McConville lived in one of the DIVIS towers, those were buildings for social housing and a Catholic stronghold. There was an British army observation post on the roof of one of them, that could only be reached by helicopter.

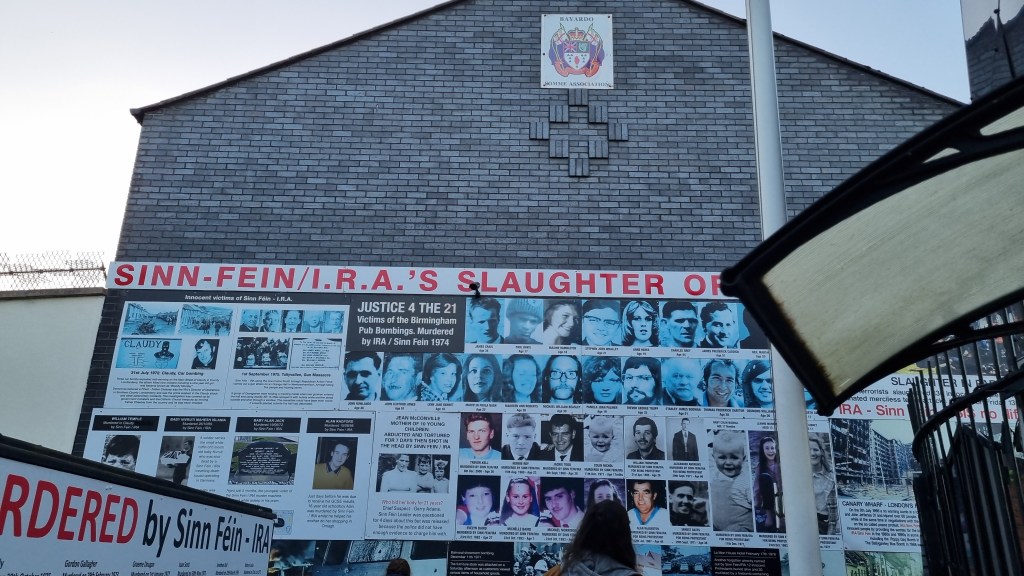

During the first years, for the British government, the Troubles were an internal matter only. They refused to take into account Dublin’s opinion until 1973, when the Sunningdale Agreement was signed, which created a new Northern Ireland Assembly. This gave a voice to both sides and a role to the Republic through the creation of the Council of Ireland. Sunningdale therefore marks a real paradigm shift, with a first agreement signed jointly by the British and Irish. This principle remained for future agreements. But Sunningdale was a source of conflict, and for the loyalists, the very principle of the Council of Ireland was unacceptable. As a response, a general strike- especially the refineries – was then orchestrated by the unionists who controlled the economy. At the same time, the UVF detonated 3 car bombs in Dublin and one in Monaghan. There were 33 dead and hundreds injured. It is the deadliest attack of all the troubles. The IRA responded to this in November of the same year with two explosions in pubs in Birmingham, killing 21 people and injuring 182.

Nevertheless, negotiations continued in the background and the IRA announced a ceasefire in May 1975. It didn’t last long, and by the mid-1970s, it was clear that the conflict would last. And so, in order to avoid potential bombings, the daily life of the inhabitants became punctuated by military checkpoints, searches and security controls. On the British side, London organised an ulsterisation of the conflict: the security was then handed over to the local RUC, which was cheaper for the British than sending valuable trained NATO soldiers.

Northern Ireland is being threatened by a small group of terrorists, so the crystal clear official narrative. Members of the IRA were portrayed as common criminals, not political activists. As a logical consequence, prisoners lost their status as political prisoners. The narrative on the British side thus made the IRA the only problem, and it succeeded because this is exactly how the Troubles were perceived in the rest of Europe.

Well aware that the conflict would last, the IRA underwent reforms, and created the « Sinn Fein » party that from this moment on gave the underground paramilitary movement an official and legal political voice.

In 1976, the Peace People were created. It was an women organization for peace using marches. Mairead Corrigan and Betty Williams won the Nobel Peace Prize for their actions. The movement did not meet with the expected success, but the Nobel Prize money has enabled their organization to create interfaith schools, among other things.

The turning point came from prisons in the early 1980s. IRA prisoners had repeatedly called for the restoration of their status as political prisoners. Their demands include the right to wear their own clothes, to be exempted from compulsory labor, to be able to gather together, and to receive packages and regular visits. To make themselves heard, they first refused prison clothes and dressed only in their blankets, hence the nickname « blanket prisoners ». They then adopted the « dirty protest », which consisted of not emptying nor cleaning their bucket of excrement, which accumulated in the cell. They held out like this for several years but were met with little media attention. The IRA prisoners in the infamous Block H therefore decided in 1979 to use the only tool still at their disposal, namely the hunger strike. On the 27.10.1980, seven prisoners began a hunger strike. London offered concessions on clothes and bought new clothes for them but didn’t give them their clothes back. The prisoners stopped their strike, but felt duped.

A second hunger strike began on 1.3.1981, this time in a cascade : one prisoner started each week, in order to keep the action going as long as possible. Bobby Sands was one of them. During his hunger strike, he ran for the Westminster parliament and won from prison, his victory giving him a huge media platform. Messages from all over the world began to arrive in London in support of the prisoners’ requests. Margaret Thatcher did not give in, especially since the IRA had struck at the very heart of royalty 18 months earlier with the assassination of Lord Mountbatten and his family. Bobby Sands died on May 5, 1981. His funeral was broadcasted and watched by 100,000 people, making him a de facto political prisoner. Several other prisoners died after him, and then the death toll stopped as the families asked for medical treatment. Soon after, London acceded to the prisoners’ demands.

The election and the death of Bobby Sands were a double trauma and induced a double paradigm shift. On the Irish side, trauma because people were shocked to see that Thatcher had left one of her MP’s die in prison ; and a paradigm shift because they realized that the political route had a much better chance of success than the paramilitary route. On the British side, trauma, because people were shocked to see that someone who many considered to be a common criminal in line with the official discourse enjoyed such popular support that he could be legally elected to Westminster ; and a paradigm shift because one had to A qualify this support as political and B count with Irish and Catholic voices in the future in Northern Ireland. Moreover, the Catholic/Protestant ratio began to reverse at that time, a trend that was officialized in the 1991 census. Irish consciousness became visual as urban murals – until then the prerogative of the Loyalists – began to appear on the Republican sides of the cities.

The hunger strikes thus marked a real turning point, even if it would take another 17 years to reach the Good Friday Agreement. Indeed, from that moment on, the violence did not stop, but neither did the negotiations. Why did it take another 17 years to reach an agreement? Well, because on the one hand there were powerful forces on the English and Protestant side who were holding back a power-sharing with the Irish and their step up. And on the other hand the IRA was not at all ready to abandon violence.

The early 1990s saw a tripartite approach to negotiations, which took into account :

• The two communities in Northern Ireland

• the north/south relations (Northern Ireland/Republic)

• the east/west relations (island of Ireland/United Kingdom)

The mere fact that the unionists accepted these parameters of negotiation changed the situation, because it meant that they de facto recognized a real role for the republic and the nationalists in the resolution of the conflict.

With Clinton’s election, the U.S. entered then the negotiations as a powerful mediation force. Another decisive force was Tony Blair, who came to power in 1997 with a vast majority behind him, at a time when the Unionists were weakened on a parliamentary level. On 31.08.1994, the IRA announced the end of armed operations, but the question of its decommissioning poisoned and slowed down the end of the negotiation process. The joint forces of Blair, Clinton, Hume, Trimble and Adams would eventually bear fruit (and bring the Nobel Prize to Hume and Trimble), as the various parties in negotiations finally reached an agreement on April 10, 1998, Good Friday. And this despite the opposition of the DUP, the party of Pastor Ian Paisely, which were opposed to the agreement, as a matter of principle. But a referendum in Northern Ireland ratified the agreement on 22nd May with 71.1% of the vote and 81% turnout. However, this large majority hid a deep divide, since it is estimated that 96% of nationalists voted in favour against only 55% of unionists. In the Republic, on the other hand, an overwhelming majority of 94% voted in favour of the agreement.

- An own government for Northern Ireland

- The creation of North/South (Northern Ireland/Republic) and East/West (Ireland/United Kingdom) institutions

- The dissolution of the RUC in favour of the creation of a joint police force

- Amnesty for ALL political prisoners

- The possibility for all NI inhabitants to have dual nationality,

these are the main pillars of this agreement. This was a huge leap of faith on both sides.

After the 1998 agreements, it was not until 2005 that the IRA finally decommissioned under the supervision of the clergy. And then the 2007 elections finally lead to a unity government in Northern Ireland, with Ian Paisley and Gerry Adams in the same government. This would have been unthinkable 40 years earlier.

All is well that ends well? Some answers in the next article: « Belfast in 2023 »

Tres vrai and deeply thought through

J’aimeJ’aime